Money talks

The peculiar case of Havana’s economic culture

Economy shapes place. Our every interaction with places can be traced back to its economic origins: who is funding this amusement park? how are you paying for this coffee? where did you find out about this shop? what is driving these developers?

In the world of capitalism, we’re used to the influences of private economic interests – we live in a world of big brands and bold advertising, where money is a formal matter and we let big business be our guide. We have big chain restaurants, big branded public spaces, and big private developers.

Cuba, however, is a communist country. It is also tightly politically controlled, with a culturally casual approach to currency and exchange. Naturally these factors play a significant role in the way places are shaped and experienced in Havana. Here are a few ways in which Cuba’s political-economic context is creating the economic culture of Havana.

The ban on advertising

Coming from the world of branding and advertising, it takes a beat to get used to the fact that there are simply no adverts to be found in Havana. This isn’t so much a cultural choice: non-governmental advertising on television and in physical spaces is banned in Cuba.

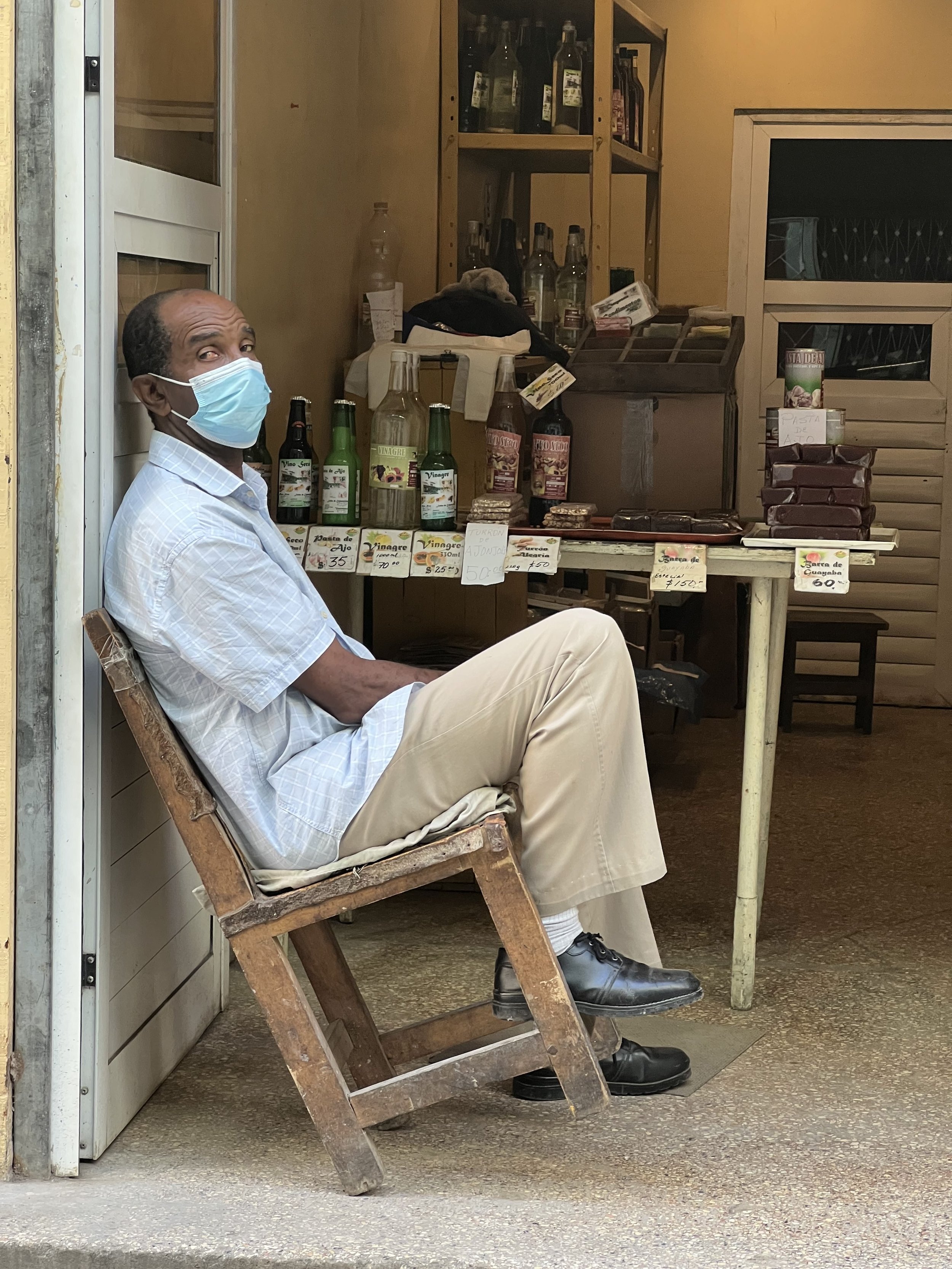

The impact of this on the city experience is far-reaching. The absence of posters and billboards may sound like a welcome relief to some, but it creates a vacuum of information about important goods and services. The absence of brand communication applies similarly to wayfinding and signage; it is difficult to tell a shop-front apart from someone’s living room; it is impossible to identify a bus stop without joining a queue and hoping.

While for visitors, this creates a baffling city experience, for locals it inspires something else entirely. Indeed, the people of Havana form a complex network of connections and word-of-mouth recommendations. Everyone knows someone who knows someone who can help, and this city-wide co-dependence seeds a sense of belonging and community that is quite special to Havana.

Informal exchange

Cuba has a closed currency, and runs almost entirely on cash. In Havana, cash points are few and far between, and no one will offer you a card reader when you come to pay the bill.

As a visitor, this is a complex landscape to navigate. The Cuban Peso is now the sole currency of Cuba (having merged with the Convertible Peso in 2021), yet street vendors will freely accept Euros, Pounds and even US Dollars. This culture of constantly swapping currencies means that basic costs, values and exchange rates are fluctuating all the time.

For Havana locals, this of course represents an opportunity to profit from cash-rich tourists. It also, however, inspires an engrained spirit of reciprocity between members of the community. In this economy, locals pay bills with favours, free services and shared business. It may not be a great wealth generator, but it seeds trust throughout the city community.

The question of tourism

While the grassroots, economic culture of Havana is built on informality, reciprocity and community, there is the inescapable, looming challenge of tourism hanging over the city.

Cuba has had a dappled relationship with tourism over the decades. Historically cautious about foreign influence on the island, until recently tourism has been viewed by the government mainly as an economic necessity.

In the past decade, however, this has changed. Now positioning tourism as Cuba’s major economic opportunity, the Cuban government has encouraged vast investment in the renovation and creation of large new hotel districts in Havana. The Grand Packard, the Gran Hotel Manzana Kempinski, and the Accor Paseo del Prado all rise, shining, on the Havana skyline. They are impressive, beautiful and inviting.

Around these hotels, luxury shops, and boutique cafés and restaurants are growing rapidly. It is a reassuring, familiar place for visitors. However, these 5-star empires provide a stark contrast to the underinvested informality of Havana proper. It is clear that government investment is pointed in one direction only, and if this continues, the people of Havana may well find themselves falling through the cracks of their resourceful, informal economic culture.

The challenge of the future

Facing high inflation, shortages in food and energy, and under-investment in residential areas, it is clear that Havana needs change.

Having suffered immensely during the Pandemic, tourism may well be the lifeline that the city needs. However, in a place where culture is so closely tied with economy – defined by principles of reciprocity, informality and exchange – development in the one may well mean adaptation in the other.

One cannot help but feel that the current uneven distribution of investment in tourism is risking future cultural alienation among locals.